These are stressful times. Covid, convoys, skyrocketing rents and grocery bills, and increasingly strange and unpredictable weather—all of it is enough to make some of us want to crawl back to bed and shut the world out.

But even in the muck in which we find ourselves, there’s an opportunity to create a kinder, more equitable world.

Gestures of goodness are happening all around us, every day: people are stepping up to demand housing for those who have none; Nova Scotians recently raised thousands of dollars to help support solar installers whose livelihoods were suddenly under attack; and most of us are doing our very best to contain the spread of Covid, so that people can get their long-awaited surgeries and our kids can go to school.

Last week, I participated in a lively panel discussion hosted by the Ecology Action Centre, which explored how best to regulate Nova Scotia Power, a private utility owned by the multinational Emera Inc. Tom Webb (an expert in co-operatives) and I spoke about the need to not only better regulate the utility, but also to rethink how we get energy. It’s time to ask ourselves whether Nova Scotia Power’s goals are fundamentally at odds with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting the environment, addressing energy poverty, and keeping the lights on (even during small storms).

Colin Rotsaert, a friend of Sierra Club Canada, shares how Nova Scotia Power’s decision to go after more profits for its shareholders at the people’s expense is an opportunity for us to rethink and restructure how electricity is produced and distributed, not only in Nova Scotia, but throughout Atlantic Canada.

I encourage you to consider these ideas and reflect on the world you want to live in—and help create.

—Tynette Deveaux, Beyond Coal Atlantic Campaign

Sierra Club Canada–Atlantic Chapter

More than Anything, a Transition to Clean Renewable Energy Requires Energy Democracy. Here’s Why.

by Colin Rotsaert

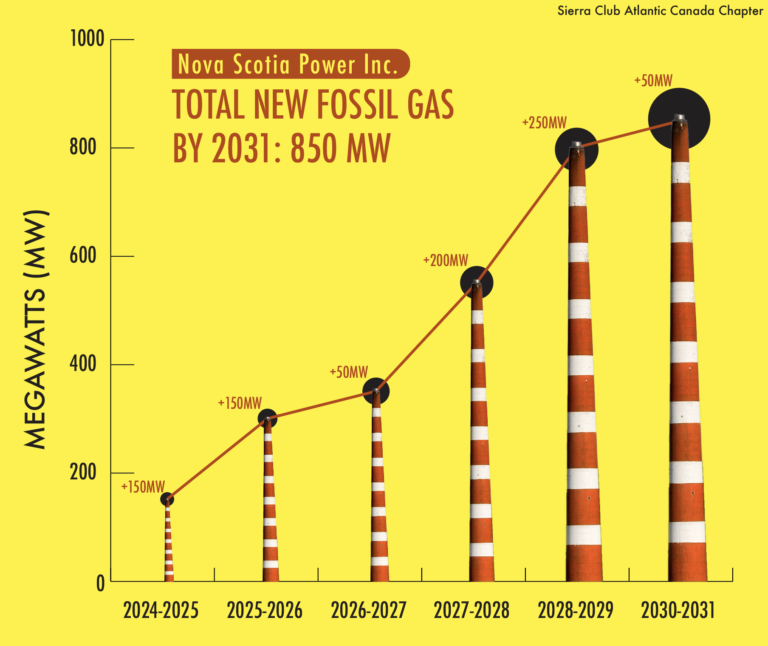

Public anger is still running high after Nova Scotia Power Inc revealed its plan to impose a new renewable energy system access fee, which threatened to crush the burgeoning solar industry in the province. While Tim Houston’s Progressive Conservative government stepped in to save the solar industry, the corporation’s proposed 10 percent rate hike for Nova Scotians is still on the table. So, too, are other schemes that would place more of the financial burden of transitioning to renewable energy on the backs of Nova Scotians. A new Storm Rider charge would see customers pay more to cover costs associated with restoring service following major storms.

The same day that NSPI announced it was applying to the provincial regulator to make these changes, we learned the company planned to further delay the shutdown of coal-fired electricity in the province.

The irony of customers paying Nova Scotia Power extra to cover the financial impacts of extreme weather events (made more frequent and severe by climate change—which NSPI is failing to address) has not been lost on Nova Scotians.

Patrick Yancey sums up this moment beautifully in a letter to the editor:

“This utterly tone-deaf move comes not only when regular folks are struggling with mounting inflation and suppressed wages, but also when NSPI is giving away millions to top execs and shareholders — all the while planning to burn more climate-killing coal for years. Over all the public shock, disgust and outrage, a singular truth clearly shines through: it’s time to deprivatize our power grid, to take the power back.”

But what would taking the power back actually look like?

Sure, deprivatizing the grid could mean nationalizing Nova Scotia Power as a Crown corporation again, but is that really the best and only option? Crown corporations and regulatory boards can claim to represent the people, but they are not actually accountable to the public. Too often these “public” corporations fall prey to political patronage appointments, ineffective regulations (and regulators), incompetence, and corruption.

Take a look at BC Hydro’s Site C Dam or the Muskrat Falls mega-hydro dam in Labrador. In 2020, a NL Commission of Inquiry into Muskrat Falls’ endless delays and billions in cost overruns by the Crown corp Nalcor released its report: Muskrat Falls—A Misguided Project. NB Power, another Crown corp, is doubling down on a nuclear future, requesting a 25-year extension on its operating lease for the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station. It also supports Small Modular (Nuclear) Reactors, a super costly technology that doesn’t exist commercially anywhere in the world, and even conservative estimates predict it would take 10 years or more to get them up and running in New Brunswick (i.e. too little, too late).

Like multinationals, Crown corporations can and do make us pay for their costly mistakes. They, too, trample on Indigenous rights and trash the planet in the name of so-called “green energy.”

We can do better—and we must. We need a system that is held much closer to the people. This requires getting beyond the false choice of privatization vs. nationalization and looking to alternative models that can support greater energy democracy.

Denise Fairchild, author and editor of Energy Democracy: Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions, tells us that “energy democracy is rooted in the long-standing social and environmental justice movements and is a key component of the evolving economic democracy movement.” The idea is to move beyond calls for a purely technological fix to the climate crisis and instead asks, “Who will develop and control clean renewable energy, to what end, or to whose benefit?”

As Fairchild explains, “The struggle is not simply to decarbonize the economic system, but to transform it.”

There is no set definition of what energy democracy means, but it generally revolves around the following principles:

· Democratic Control and Participation: Ordinary citizens are empowered to have much greater participation in energy policies.

· Public and Social Ownership: The utility operates to serve the needs of a community, not the profits of shareholders. Public ownership can take the form of municipal energy utilities or citizen- and worker-owned cooperatives, with lots of room for collaboration between the two.

· Renewable and Local Energy: Though public ownership sometimes refers to nationalization, “local power” tends to lead to a faster and more just transition to renewable energy.

Energy democracy isn’t some abstract theory; hundreds of communities across Europe and North America are already practicing energy democracy to varying degrees. Whether it’s rural electric cooperatives in the US, or municipally owned energy grids in large European cities like Hamburg, the proof is there.

We even have local examples here in Nova Scotia. The towns of Antigonish, Berwick, and Mahone Bay all somehow managed to hold on to their municipally owned utilities during the frenzy of privatization in the 1990s. In 2014, they partnered together to create the Alternative Resource Energy Authority (AREA), a 100 percent municipally owned company spearheading community solar gardens and the Ellershouse Wind Farm.

So how do we take back our power?

First, you have to want it—and be willing to say so. If we can’t imagine a better future, we can’t even try to make it happen.

But is it realistic? Before you answer, ask yourself this: Is it realistic to expect a multinational corporation that is beholden to its shareholders around the world to lead the way on a rapid transition to clean, renewable, and reliable energy? And if it could, what would be the cost to the environment, Indigenous and community rights, and those living in energy poverty?

Let’s find the courage to talk about a future that includes energy democracy and actually meeting targets to reduce greenhouse gasses—a future that protects the environment and is concerned with people’s wellbeing.

In the coming weeks, Sierra Club Atlantic Canada will be organizing opportunities for you to learn from those who are blazing trails for a better future. We hope you’ll join us.

Colin Rotsaert lives on Cape Breton Island and has a longtime interest in creating more cooperative and ecological communities.