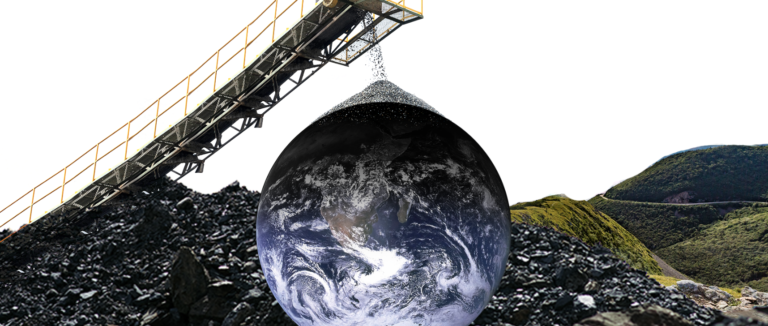

The reopening of Canada’s only underground coal mine in September 2022 reignited a host of environmental, health, and safety concerns. The Donkin coal mine in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, ceased operations in March 2020, following repeated stop-work orders and more than a dozen roof collapses in just a few years.

So what’s changed? Certainly not the geological conditions that make the mine unsafe for miners or the coal mine’s carbon footprint.

• Did you know? Donkin mine factsheet

• Donkin coal mine needs to be shut down for good

• Submission to Minister Tim Halman appealing the Industrial Approval renewal for the Donkin Mine

The answer lies not in Nova Scotia but abroad. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, coal prices have soared. Now the mine’s owner, Kameron Collieries ULC (operating locally as Kameron Coal), is cashing in on this latest fossil fuel bonanza.

Nova Scotia cannot achieve its greenhouse gas reduction targets and mine coal. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that coal combustion is “the single largest source of global temperature increase.” The IEA and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have both made it crystal clear that countries must rapidly transition away from fossil fuels—particularly coal—if we are to have any chance at containing global heating to 1.5°C. By allowing the Donkin mine to reopen, the provincial government is either saying they don’t believe the science that the IPCC and other international bodies have put forth—or, they’re saying, “Let the Hunger Games begin.”

Despite the claims that the Donkin mine would only produce metallurgical coal to make wind turbines, the high price of thermal coal means that the coal is more likely being sold to burn for electricity.

The Donkin mine also produces metallurgical coal, which is used in steelmaking. Metallurgical coal is mined at deeper depths and produces even more greenhouse gas emissions per ton than thermal coal.

Moreover, new research shows that mining coal emits 50 percent more methane into the atmosphere than previously thought. Methane is a more potent and fast-acting (i.e., atmospheric-warming) greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. In fact, the impact of a tonne of methane is equivalent to between 84 and 87 tonnes of CO2 over a 20-year timeframe (see the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2017, p. 405).

The Donkin mine is the largest industrial emitter of methane in Nova Scotia and the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in Nova Scotia.

Yet for some reason, Kameron Coal has been allowed to “self-report” its greenhouse gas emissions to the province since 2017, despite the company’s own estimates that put it far above the 50,000-tonnes threshold that requires the emissions be independently verified by a third party (370,743 tonnes of CO2e in 2020, and 422,934 tonnes of CO2e in 2019).

The Donkin Mine is now a mandatory participant in the province’s new output-based pricing system, which is supposed to make big polluters pay a premium for surpassing industry emissions standards.

But it’s Nova Scotians who will pay the biggest price—with their health, their safety, and even their taxes. Each year, the Cape Breton Regional Municipality has to treat approximately 6 billion litres of waste water from Cape Breton’s abandoned coal mines for contamination. In typical provincial fashion, it’s taxpayers—not the mining companies—who are footing the bill.

As expected, Kameron Coal has been using the promise of good-paying jobs to stifle important conversations and counter community dissent. But it’s important to remember that the mine isn’t safe for workers. In 2020, Kameron Collieries ULC announced that it was ceasing operations “due to adverse geologic conditions in the mine.” Those geological conditions have not changed.

While the Donkin mine was open from 2017-2020, it ran up 152 warnings, 119 compliance orders (infractions), and 37 administrative penalties.

Just months after re-opening, the Donkin mine has racked up 14 new safety warnings, 19 compliance orders (infractions), and 8 administrative penalties—an even higher rate of safety violations per month than when the mine was open the first time.

Reverting back to “care and maintenance” (idle) mode isn’t the solution, either. The Donkin mine continued to exceed Nova Scotia’s cap for greenhouse gas emitters in the two years that it was idled.

Those fugitive methane emissions are why the Donkin mine has ventilation fans operating 24/7 at the entrance to the mine: to dilute the concentration of methane and other harmful emissions. But these same fans are giving off an incessant low-frequency noise that local residents have described as “sleep torture.”

The only way to stop the methane and other greenhouse gas emissions—and the noise from the fans—is to close the mine for good. When that happens, the mine will naturally flood, the emissions will ease, and the local community will finally be able to sleep through the night.

Cape Bretoners need good-paying and safe jobs to support their families. The provincial government must take action to deliver on its promise of sustainable prosperity. Let’s invest in a positive and forward-thinking future for Cape Breton.

Updated on February 27, 2023