While we can’t say size always matters, in the case of buildings it really does.

On Tuesday, September 7, Halifax and West Community Council will be hosting a virtual public hearing to discuss proposed amendments to the Halifax Municipal Planning Strategy and Halifax Peninsula Land Use By-law, requested on behalf of developer Peter Rouvalis. His company is proposing to build two highrises fronting Robie St, College St, and Carlton St in Halifax. The towers (one 29-storey/90 metres plus penthouse and the other 28 storey/87 metres plus penthouse) would feature 577 residences and more than 500 parking spaces in a new six-level underground parking garage. Also being discussed at the hearing is whether to approve a 23-storey highrise overlooking the Halifax Common (Westwood Tower, 2032–2050 Robie St), with underground parking for a minimum 70 parking spaces.

So what’s the BIG deal? Why should we care how high a new building stretches into the sky or how many cars can be parked in the garage?

There are many reasons, but let’s focus on these seven.

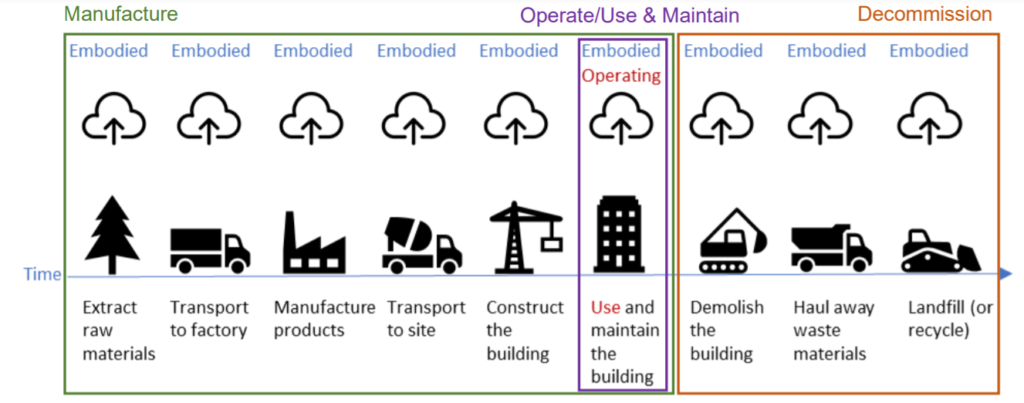

1. The higher the building, the greater the carbon footprint

Highrises have a greater embodied carbon footprint than low- to mid-rise buildings that provide a comparable number of residential and/or commercial units.

“Embodied carbon emissions account for up to 75 percent of a building’s total emissions over its lifespan.”

| 2. We need to be thinking about a net-zero future now The World Green Building Council defines a net-zero carbon building as “a highly energy efficient building that is fully powered from on-site and/or off-site renewable energy sources and offsets.”While this may sound like a thing of the future, the technology is already well established and being used in buildings (and homes) in Canada. What’s more, the money saved on energy costs “more than offsets the upfront capital costs” to achieve net-zero building standards. |

| 3. “The greenest building is the one that’s already built” The Royal Institute of British Architects recently came out strongly against the demolition of older buildings, saying the practice should be stopped in order to curb carbon emissions. It wants older buildings renovated and retrofitted instead. Even new energy-efficient buildings can take many decades of efficient operation to overcome the embodied carbon footprint of constructing the building itself.In Halifax, buildings are regularly written off much earlier than necessary to make way for something shiny and new—and a lot bigger. Why should real estate developers get a free pass on reusing and recycling older buildings? |

| 4. Five hundred more cars in downtown Halifax simply doesn’t make sense Anyone who has been in downtown Halifax in the past few years knows that it’s already congested with cars and buses. Why would we want to further add to the number of vehicles, particularly in a climate crisis? The fact that the Rouvalis highrises are designed to accommodate a six-level parking garage indicates that this project isn’t part of a broader sustainable community design that would facilitate active transportation. Nova Scotia’s transportation sector currently accounts for 35 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the province. We need to be taking steps to reduce our reliance on cars. |

| 5. Yes, we need more housing, but it should be affordable housing Taller buildings cost more to build, but they’re also more profitable for developers, who can rent them as luxury units. This doesn’t only impact the people who are evicted from older buildings to make way for new ones. As the director of Making Cities Livable International Council explains, “Tall buildings inflate the price of adjacent land, thus making the protection of historic buildings and affordable housing less achievable. In this way, they increase inequality.” In essence, there goes the affordable neighborhood. |

| 6. Just because a highrise provides greater housing density doesn’t mean it’s green In fact, because highrises require a lot of steel and concrete, they’re inherently less sustainable than mid-rise buildings built with wood (“Concrete is 10 times more GHG-intensive than wood”). Also, according to BC Hydro, highrises in that province “use almost twice as much energy per square metre as mid-rise structures.” So while greater housing density can be part of a solution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and preserve biodiversity, that doesn’t mean highrises are automatically the answer. The proposed towers would leave a huge embodied carbon footprint and worsen vehicle traffic in the downtown area. 7. It’s the law, and our elected leaders promised. It’s as simple as ABC. A) Halifax Regional Council unanimously approved the HalifACT plan on June 23, 2020. On the municipality’s website it boasts, “HalifACT is one of the most ambitious climate action movements in Canada.” What does HalifACT set out to accomplish? A lot of good stuff, actually, which could help Halifax address the climate crisis — including reducing greenhouse gas emissions. You can’t reduce these emissions by simply not counting them (that’s cheating). B) The proposed highrises (and the by-law amendments that would allow them) do not align with provincial legislation. |

| Nova Scotia’s new Sustainable Development Goals Act (SDGA) states: “This Act is based on the following principles: (a) the achievement of sustainable prosperity in the Province must include all of the following elements: (i) Netukulimk, (ii) sustainable development, (iii) a circular economy, and (iv) an inclusive economy” |

The SDGA defines sustainable prosperity as “prosperity where economic growth, environmental stewardship and social responsibility are integrated and recognized as being interconnected.” It defines circular economy as “an economy in which resources and products are kept in use for as long as possible, with the maximum value being extracted while they are in use and from which, at the end of their service life, other materials and products of value are recovered or regenerated.

While an actionable plan for the SDGA is still being worked out, the principles set out in the Act are now law.

C) Canada is a signatory to the Paris Climate Agreement (2015), the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (2016), and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015 by 193 countries.

Although the details may vary, each of these agreements has one thing in common: a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

It is not only the federal government that is bound by these agreements; the provinces are too.

So the question is:

Will Halifax and West Community Council (and Halifax Regional Council) honour the HalifACT plan, Nova Scotia’s SDGA, the Paris Climate Agreement, the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals?

This is a simple Yes or No question.

| Sierra Club’s Atlantic Canada Chapter has put the question to Halifax Regional Council and the Halifax and West Community Council. We’re looking forward to their reply, and we’ll be sure to share it with you. For more on embodied carbon in the building sector, check out our report, #SizeMatters. To find out more about the virtual public hearing on September 7 at 6pm AT (including how to participate) click here Thanks for reading, Tynette |